Despite sensational headlines, where we are in the VC-startup cycle seems like a reasonable and rational outcome from ’20 and ’21

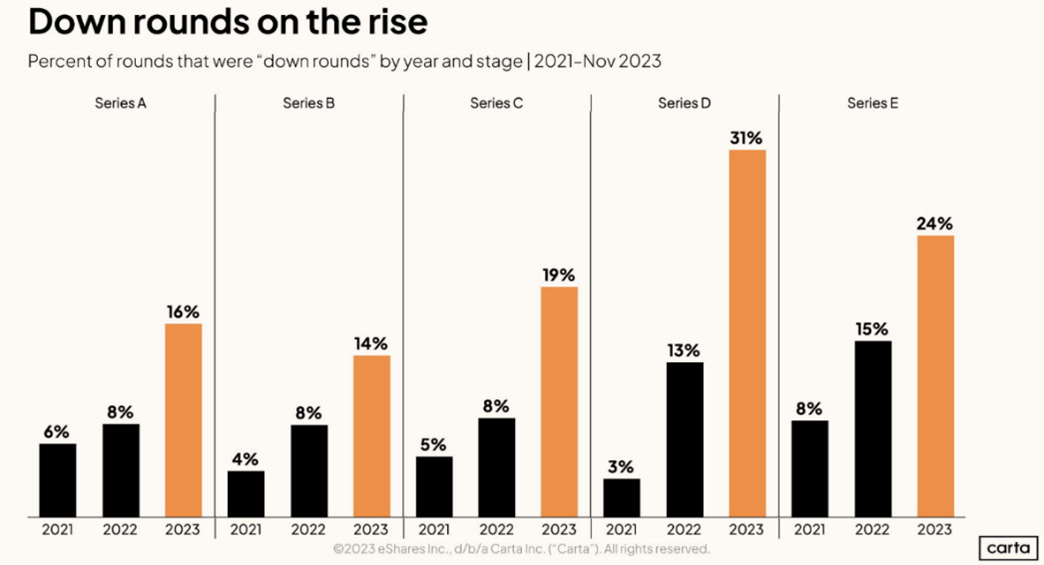

Sensational death-of-startups headlines (CNN, Globest, SF Chronicle, Business Insider, for starters) could make you believe that startups and tech are done for. In their defense, the data some of them point to isn’t pretty:

(Silver lining: in true startup form, even startup failures can create venture-backed startups!)

In all seriousness, though, as a venture investor, I think many articles and posts – and the general narrative around shutdowns, extinction-level startup events, layoffs, and valuation corrections – don’t tell a complete story. As hard as it may be to believe, it may not be as bad as people think (or certainly not as sensationalized as what many pubs may be leading their readers to believe).

What Got Us Here

An oversimplification of what happened during ’20 and ’21 is as follows:

-

- After a period of initial uncertainty (and volatility), COVID pulled forward a ton of growth for tech companies, fueled by a combination of increased demand and need for digital tools with a meaningful injection of capital via COVID stimulus

-

- VCs and other investors rewarded growth handsomely – some may say ‘at any cost’ – and startups raised capital in droves

-

- Valuations increased to accommodate for these faster growth trajectories, faster ‘product-market-fit’ cycles, and more rapid software and tech adoption

-

- Shifting to the public side, as growth rates for big public tech companies also barreled on, their market caps skyrocketed. In October 2022, FAANGM accounted for over 1/5th of the total US market capitalization on the NYSE.

-

- Valuations increased to accommodate for these faster growth trajectories, faster ‘product-market-fit’ cycles, and more rapid software and tech adoption

-

- VCs saw the massive growth and bigger outcomes/market caps, paths to liquidity, and larger markups in their portfolio faster than they’d maybe ever seen (at a minimum since the dotcom era, if they’ve been around that long) and raised more capital to fund and own the growth opportunity

-

- At the same time, liquidity valves opened. SPAC-mania happened, IPOs popped, and all of the pent-up dollars invested in late-stage private companies had the potential to be liquid again.

-

- The influx of VC into the startup ecosystem, bigger outcomes, and record liquidity potential largely outpaced the growth of financings. This caused competition for the best deals to increase, and investors reacted by writing bigger checks earlier, at higher prices. Valuation is a nail every VC can hammer, and hammer it they did. It’s also a lot easier to underwrite higher entry prices when outcomes appear as big as they are. This ultimately changed the investment game from “invest > derisk business > invest > derisk business > etc.” to “invest huge > startup skips rounds and derisking > raises much later, if ever”. We’ll revisit the implications of this momentarily.

It seems obvious that the music was going to end sooner or later. Round sizes, valuation multiples relative to traction, and growth rates simply weren’t going to be sustainable over the mid-to-long term. Once inflation entered the chat and the Fed raised rates, it was game over for the frothy times and signaled the beginning of the corrective period we find ourselves in. Rather than leave it at that, though, I’d like to dig into what that ‘correction’ really is and how it manifests itself as shutdowns and re-pricings.

“Correction” Impacts: Shutdowns

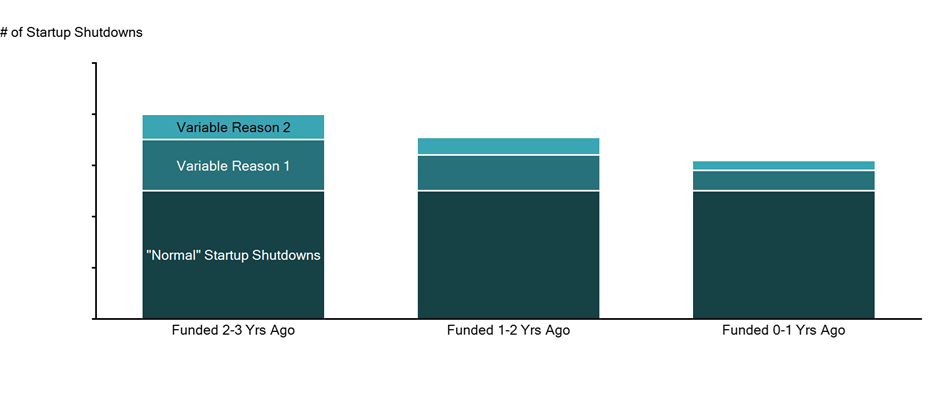

I think about the reasons for startup shutdowns year-over-year as a series of stacked bars, where the X axis is years/time and the Y axis is the number of showdowns. Each layer of a year’s bar is a reason for the shutdown.

In any given year, investors deploy capital into startups. Those startups typically have a year or two to figure out if they’re on to something before they need to make the decision to raise capital, shut down, or operate without needing to raise money. That also means that in any given year, there is a cohort of companies that were likely funded 1-3 years ago at that fork in the road. The startups that raised 2-3 years ago are likely the largest cohort of companies at that fork, with those funded more recently likely having a bit more runway. The companies at the fork in the road every year will inevitably see some companies go out of business as the products, services, or markets they were trying to create didn’t pan out and they eventually run out of cash. That is a completely normal – and expected – result for high-risk venture-backed companies. VCs take massive risk, and the oft-cited 90% startup failure rate is real. Every year startups will shut down because the risks they take in creating new products, services, markets, and industries don’t bear fruit. Again, this is normal and expected.

If we look back over the last several years of venture financing data, we see that the number of pre-seed and seed deals in Q1 and Q2 ’22 are well over double what they were in Q4 2023, and meaningfully higher than the historical median deal count.

Given the increased number of startups funded in ’21 and ‘22, it also seems reasonable to assume that this year’s ‘fork in the road’ cohort (2-3 years since they were originally funded) will be larger and that there should therefore be more shutdowns (assuming a similar percentage of failures as prior years).

I also predict that the failure rates for startups will be higher in this ‘COVID Cohort’, as investor discipline and general underwriting both seemed lacking relative to prior periods when cash was more expensive. *Note that my view on this is relatively narrow, and probably more pronounced as the deals we tend to see are those focused on the PropTech space, where the interest rate environment has a more direct and lasting impact*. That cohort can be visualized as another layer on the stack as a ‘variable reason’ for startup failure, representing outsized failures relative to prior years when investor discipline was more rigorous. These startups broadly represent those that probably shouldn’t have received financing to begin with. Investors plowed a bunch of capital into startups that burned the cash in favor of top-line growth without being able to prove sound unit economics. They traded $1.00 for $0.90 and are now failing. Investor exuberance and expectations of everything going up and to the right imply this layer will be more meaningful than in prior years, as the data is beginning to support.

It’s also worth noting that this cuts both ways: 2-3 years after ‘slow’ or ‘down’ years of VC, we will also expect to see fewer failures. Does this mean that startups and tech have turned around? Probably not. It just means the absolute number of shutdowns is correlated with prior years’ venture financings. The more meaningful shutdowns to mention are those that are specific to a particular technology or industry. In the early 2000s, VCs poured a lot of money into CleanTech startups, with the vast majority of those eventually failing. It was a fledgling industry and much of the new tech didn’t pan out. The conclusions from that were that the sector wasn’t ready yet and that there would likely be a pullback in funding to focus on smaller, earlier-stage technologies and tests.

If you replace ‘CleanTech’ with ‘SaaS’, however, you’ll see a bit of a different story: while many early SaaS companies also failed, the business model and investor experience both evolved, and I hypothesize that both the funding and failure rates of companies in that space have since dropped to more predictable levels (this will vary across industries, but I believe the failure rates at a high level have dropped). It’s the outsized, early testing of a space that can lead to an outsized failure bump, visually represented as ‘Variable Reason 2’ above (also note that there could be several industries that get hot in a given year, so we may go up to Variable Reason 10 in some years, and perhaps not have any in other years). I don’t have the specific numbers for this year, but I’d imagine that we saw more concentrated failures in crypto in ‘22, offset by booming investment in AI that may see an increased number of shutdowns in the next 18-24 mos.

Re-Pricings and Valuation Drops

I mention a segment of companies above that perhaps shouldn’t have received financing to begin with. I’ll also argue that there’s a segment of startups that shouldn’t have received venture financing, or be priced at multiples based on outsized future potential. This segment of startups wouldn’t necessarily outright fail, but they would ultimately be subject to massive re-pricings once the smoke cleared from the high-flying times of ’20 and ’21.

Going a bit further, in the PropTech space I believe that the root cause of the valuation drops and re-pricings is more due to investors believing that a startup had higher margins, more differentiated products, services, and business models than they really did. Investors now recognize that many PropTech startups are either transactional in nature, very sensitive to interest rates, or otherwise have technology layered onto service-based businesses that don’t move the profit margin or growth needles. In my corner of the world, I also see startups that might have high capital intensity. When capital gets more expensive, as we’ve seen in the current rate environment, the costs can outstrip any potential for profitability and sink a startup. Transactionally-driven companies are also susceptible to their revenue going to zero. There’s a point for a customer where below it, a transaction doesn’t make sense. For example, a home buyer may require a mortgage whose monthly payments in a high-rate environment exceed their ability to repay it (or qualify for the loan to begin with). It’s a relatively binary outcome at that point – the buyer can either buy the home or not, and when homebuyers are spread across a continuum of their abilities to purchase, interest rates can dictate the velocity of transactions. Investors seemed to have ignored these types of risks for a period of time, but they are now featured prominently in valuation methodologies and driving valuation drops to correct for them.

There were also companies that may have been operating for several years of slower growth and lower margins that caught a COVID tailwind and saw outsized growth. We’ll discuss an example of this later, but we observed a fair number of investors rewarding those companies with capital, valuations, and multiples that assumed that growth rates would remain in an elevated state and that margins would continue to climb. When margins and growth slid back to historical averages – or worse, as a bunch of growth was pulled forward and there could be a year or two lag for things to catch back up – it became clear that the valuations some of these companies enjoyed weren’t going to result in wins for investors.

These dynamics also led to a slew of startups that we often refer to as having a ‘valuation overhang’, where a startup may have raised a fair amount of cash, but with the new implied growth rates, efficiency metrics, technology differentiation, and valuation multiples from investors, they have a long path to even growing into the current valuation. These startups face tough decisions around whether they should raise additional capital, as a new investor would likely reset a valuation and create high management team dilution (made more onerous with investor anti-dilution protections), perhaps to a point where founders would no longer be motivated to create the type of exit that investors want. The alternative is that management teams take their chances growing with the cash they have and try to get to profitability, where they are afforded time and a ‘default alive’ status where they still have a chance at meeting or exceeding their prior/current valuation or have a fruitful exit. Or there may be a recap of the business where the company technically survives, but existing investors are largely wiped out. Once a pref stack reaches a high enough point, a startup may find itself ‘un-fundable’ as future investors begin to worry that a required exit size would be too large and that the odds of them getting any capital return wouldn’t be worth the risk.

A Hypothetical Example:

Let’s suppose that it’s 2018 and you start a business managing properties. Peers in your industry generally earn mid-to-high single-digit net income margins, have light debt burdens (if any), and rely on labor to deliver services. Your margin profile reflects your ability to use off-the-shelf technology and software to remain competitive, lean, and earn median profit margins.

Now let’s say that a global pandemic happens, and suddenly demand booms for your services as capital gets infused into the economy, interest rates are nearly zero, and transactions are happening rapidly. It seems as though everyone is looking for skilled property managers to operate their properties as portfolios grow. This tide is raising all ships, and your growth is outsized relative to prior years. Clients are also willing to pay more for your services, as demand for units and homes increases and rents rise. There are few managers that have track records and you benefit from these tailwinds.

Investors (perhaps VCs) recognize the newfound explosive growth in your industry, and you position your business as ‘technology-enabled’. VCs reward your outsized growth and higher profit margin with a rich valuation and a boatload of cash to help you grow and take over the industry. Life is good.

All good things come to an end, though, and after a solid run of a year or two, interest rates rise, rents stabilize, and your technology-enabledness drifts back to the steady-state profit margins of your industry. Growth goes back to normal.

All-in-all, this doesn’t feel like the worst situation for you! Sure, you may own less of your business as a result of the capital you raised, but the business is more or less operating as it should. But there’s a catch! The valuation that VCs rewarded you for feels far-fetched. At market multiples, you need to grow 2-3x for the next 2-3 years to sniff that number. Unfortunately, you can’t find efficient ways for cash to drive that kind of growth. In fact, you’re now burning cash as you over-hired for growth that never came, and it’s pushing your company to bankruptcy without drastic changes. RIFs and cost reduction measures are instituted – maybe a bit too late – and the business shrinks. Employees leave and you’re faced with the same growth requirements but with a fraction of your staff. In the end, you decide to shut down the business in the form of a ‘soft landing’ via a sale to a competitor that will take over servicing your clients. You stay on board for the next 9-12 months to ensure a smooth transition, but investors are disappointed, and you didn’t get the big outcome that you hoped for.

What a ride! The above isn’t exact by any means, but it highlights the evolution of a business in more or less competitive stasis, or perhaps non-differentiated in its industry, that raises VC and eventually gets pushed to the brink. These are the types of companies mentioned above as being ‘miscategorized’ by investors as having venture-backable products, services, or business models when they really didn’t. In my opinion, there are a lot of companies with a history that rhymes with this story.

Closing

The headlines are sensational and the data isn’t great, but I don’t believe that it’s as bad out there as people are being led to believe. The shutdowns in the startup and tech ecosystems that we’re seeing now are a rational outcome of investor exuberance and a period of outsized growth paired with cheap capital. The music was going to end sometime, and that time was right about 2022. While shutdowns, valuation drops, and layoffs will snag attention, there is still hope. AI and new technologies will continue to mature and attract investors, and bubbles will continue to form and pop. It’s what makes the startup ecosystem, and the investors that drive it, a lucrative and exciting place to play. Sometimes it hurts, as we’re seeing now, but I know I’m not alone in believing that brighter days are to come.

The information provided in this blog is not intended to be financial advice or solicitation for any purchase or sale of securities and is the opinion of the author at the time of publication. Investing in securities entails risk, including the risk of principal. Some of the information presented has been provided by third parties, has not been independently verified, and is subject to change without notice. The opinions stated are the opinions of Nine Four Ventures at the time of publication. Past performance is not a guarantee of future returns.