Predicting the impact on agents, commissions, and more

Today’s Thesis Driven is a guest letter from Kurt Ramirez, General Partner at Nine Four Ventures, an early stage proptech fund.

In October of 2023, a series of court decisions lit the fuse for a powder keg of change impacting residential real estate transactions in the US. The rulings go into effect on August 17, 2024, with a potential blast radius that touches consumers, agents, the National Association of Realtors, startups, lenders, and most parties involved in a transaction. The rulings have generated an immense amount of conversation, concern, and uncertainty across the industry, particularly with practitioners. As a VC, however, I see the rulings as catalysts for change that I expect will build on momentum from tech companies and startups already chipping away at industry transformation.

Starting this month, the rulings will dramatically reduce the overall size of the real estate commission pool. This drop will be most acutely felt by agents and brokers, driving some to leave the industry, while tech and startups take market share. This increased competition for commissions, products, and services related to a transaction will largely benefit consumers, who will benefit from lower transaction costs, greater operational efficiencies, and better overall experiences.

Today’s Thesis Driven tackles the potential impacts of the NAR settlement on the residential ecosystem, including:

- Global and historical context on residential commissions;

- A summary of the NAR settlement;

- The role of technology, startups, and changing consumer preferences;

- The settlement’s likely impact on the residential market and–in paticular–agents and commissions.

Putting Commissions Into Context

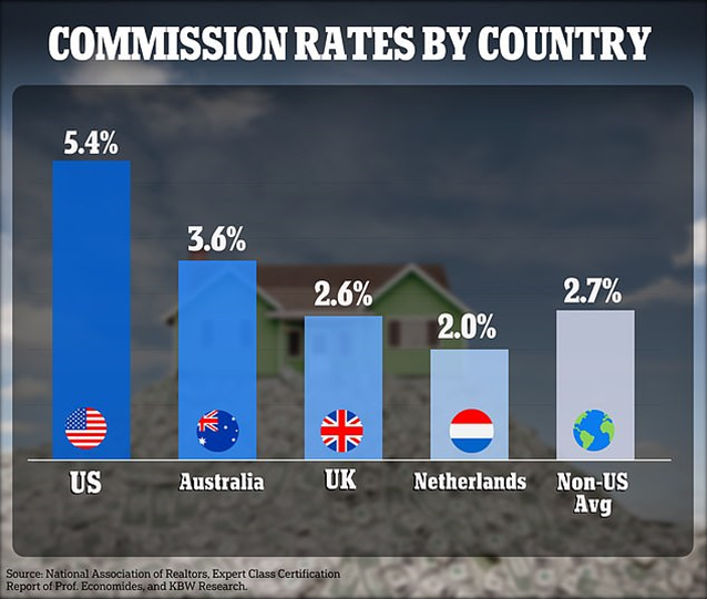

Starting at the top, it’s important to recognize that real estate commissions in the US are some of the highest in the world:

Source : NAR

These rates are also highlighted in a whitepaper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond:

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

It’s tough not to see the US commission rates of roughly 2x the non-US average and think that, perhaps, there is a way to buy and sell a home that doesn’t need to be so expensive. We can also look at the role that technology has played in other services-based industries to see how access to data, transparency, and negotiating power have led to collapsed cost structures with better customer experiences.

A pair of generally accepted examples are travel agents and financial services firms, each of which were drastically transformed by technology, leading to significantly reduced cost for consumers. It seems to me that there is a precedent for increasing the transactional efficiency of homes that bring us closer to the global average–and the US government now agrees. There’s air to let out of that balloon.

The NAR Settlement

The gist of the NAR settlement is that agent commissions are now being ‘decoupled’: listing agents are no longer allowed to specify buyer agent compensation on the MLS. Steering away from this “cooperative compensation” structure is a meaningful change: previously, an agent would list a home on the MLS with a contracted commission sharing agreement between a seller and a buyer agent, typically 2.5-3.0% of the transaction price for each side. This cooperative compensation model has some drawbacks, notably:

The cooperative compensation model creates transaction costs that are meaningful, yet indirect.

Buyer agent services are often marketed as being ‘free’ to the home buyer – I can attest to this personally – as the seller pays the buyer agent upon closing (the NAR settlement is expected to address this as well). Agents are not, in fact, free. The flow of funds is from the buyer, typically via a down payment and mortgage, to the seller, who then nets out transaction fees. The greater the transaction fees, the less a home seller nets. If a buyer doesn’t use an agent, in theory, they could negotiate a lower purchase price that nets the seller more money as the transaction costs would be lower. While the weight of the commission has historically been felt more indirectly by consumers, as they are not yet cutting a check directly to their agent for their service, the agent commissions are very real and very not free.

Agents get paid no matter what (or close to it)

MLS lock-in created a beautiful way to protect agent commissions and stave off competition.The MLS achieved this by becoming the marketplace for home buyers and sellers that leveraged classic network effects to win consumer eyeballs (the most inventory attracts the most potential buyers, which attracts the most sellers, etc. etc.). Listing a home on the MLS is also generally limited to licensed real estate agents and brokers, so as long as the MLS exists and the cooperative compensation agreement is in place, commissions are essentially locked in.

The result is that agents almost always get paid, no matter how little work they perform or the quality of their work. Even if a home buyer finds a home independently and does everything themselves, their agent is usually entitled to a full commission if they’re under contract and transact through an MLS. Similar dynamics exist on the seller side. As long as agents under contract with a seller and as long as the home sells, they’re entitled to their commission.

Agents have fiduciary obligations to their clients, yet there are potential conflicts when a commission amount is advertised.

In theory, agents should act in the best interests of their clients. However, what happens if there’s a juicier commission advertised to a buyer agent for a home that might not be the best fit? Do the homes with higher commissions move to the top of the pile for an agent, whether or not the home may be the best one for a buyer? Does a tie go to a home with a higher commission? If agents fulfill the fiduciary duties they have to their clients, then the commission they see shouldn’t matter in the same way that a buyer agent should negotiate the best/lowest price for their client.

In a less digitally native, pre-Zillow era, the current cooperative compensation structure might’ve made sense. Consumers couldn’t do as much and weren’t nearly as informed as they currently are, so perhaps there weren’t as many questions about price-to-value. The public didn’t know what inventory was available, sellers didn’t have a good way to attract eyeballs, and data was siloed, so the structure formalized incentives to drive transactions. In the digital post-Zillow-era, however, this commission structure can be seen as an artifact. Buyers and sellers can do a lot more on their own, are much more informed across each stage of a transaction, and are capable of more accurate price comparisons for most jobs an agent performs. Despite all of this, commissions are still largely a fixed price for a variable number of jobs that may be performed by an agent and/or their team at various levels of quality.

By decoupling commissions, the NAR settlement has the potential to solve some of the above. Breaking apart commissions arms consumers with the ability to negotiate independently and changes the game from consumers having less power to being armed with more tools in their negotiation toolbox (The NAR argues that buyers and sellers have always been able to negotiate with their clients. That might be technically true, but it’s been wildly challenging to pull off prior to this settlement.). At the most recent Inman conference in May there was talk on and off stage about how buyer agents now need to show the value they’re creating…imagine that! I don’t think anything could highlight the need and opportunity to pull commissions out of the buy side more than the fact that these conversations are even happening, and happening as though value has never had to be shown.

In a vacuum, the NAR settlement seems like it has the potential to empower buyers and sellers to reduce their costs and subsequently deflate the size of the commission pool. However, the settlement may represent a domino that triggers other trends lurking below the surface to emerge. These trends and newfound strategic positions of alternatives to the current agent model may have a much more meaningful impact on the industry.

The Roles of Technology, Startups, and an Agent’s “Jobs to be Done”

There’s a pair of major trends that seem particularly well-timed to converge with the NAR settlement and place additional downward pressure on real estate commissions:

- The continued evolution and maturation of startups and tech that are doing more and more of the jobs that an agent was previously hired to do

- A shift in customer preferences and willingness to pay for the services an agent provides

We’ll start with the evolution and maturation of startups and tech.If you ask your favorite AI platform what a real estate agent does, you’ll probably get something that looks like this:

Source: Google Gemini

What’s interesting to me is that there are software solutions that do every single bullet listed above. Not only that, but there have been software solutions and startups capable of doing all of the above for quite a while, yet 89% of home buyers and sellers still use an agent. What gives?

The technologist in me points to the classic “Jobs to be Done” theory introduced by Clay Christensen that says that people buy products and services to get specific “jobs” done. A real estate agent has historically been employed to do the above jobs, for example. The many ‘jobs’ that need to be done haven’t changed much in the last decade or three, they were just performed in much more manual and analog ways, and only an agent could do them. Comparables needed to be aggregated and shared, models needed to be run to determine what prices could look like, homes needed to be toured, and design partners needed to be consulted. That was all analog and offline, with data that was locked and siloed with agents and brokers. These jobs all took a lot of time and effort, and agents were the only ones capable of doing those jobs as they were the only ones with access to the necessary information. Home buyers and sellers didn’t have and couldn’t have access to that type of data to do much on their own – they needed to go through their agent gatekeeper for it.

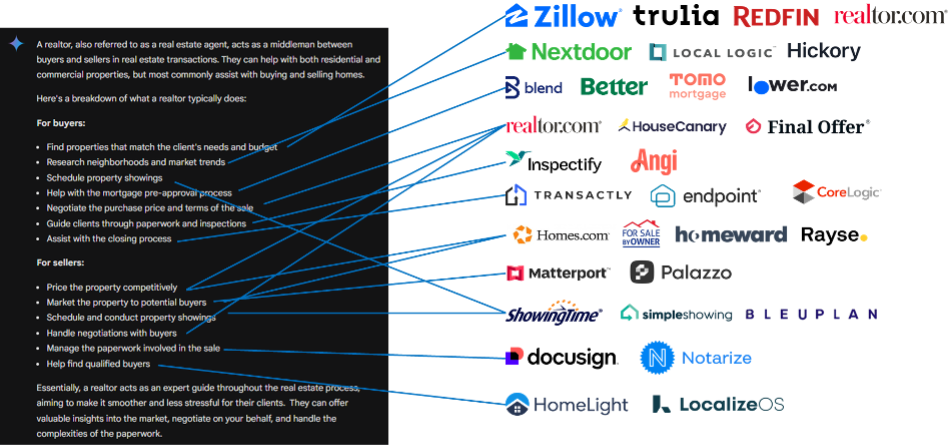

Today, however, home buyers and sellers are armed with enormous amounts of data at their fingertips courtesy of tech and venture-backed startups. Want to know what your home might be worth? Check out your Zestimate or plug it in to the automated valuation model of your choice. Want to see what a new design might look like for a home you want to buy? Redfin has that now. Perhaps you’re looking for some design inspiration? Houzz. What the latest social media influencer focused on interior design is up to? Instagram. Search Zillow or FSBO.com for homes, Policygenius to price insurance, Better Mortgage to get pre-qualified for a loan, Notarize to notarize docs, Docusign to execute and distribute them…you name it, and you can do it all digitally. I’ll argue, then, that with home buyers and sellers armed with so much data and so many tools, the number of jobs an agent is really being hired for is fewer in number and scale than it ever was. But even though an agent is doing fewer things, their commission hasn’t changed in a commensurable way.

Source: Nine Four Ventures

Why?

Well, you could argue that the commission-sharing lock-in contributed to that, which I believe is true. You could also argue that just because an agent is doing fewer things, maybe the only job that really matters is relationship-based and one that software can’t replace. For most people, there are emotional and financial components of a home purchase or sale that is likely the largest transaction in their lives. There’s a lot at stake. An agent providing the comfort and assurance that a buyer or seller is doing the right thing, paying the right price, selling at the right time, and is the best-off they can possibly be is an important piece that people appear to be paying handsomely for. Having someone to talk to along the way feels comforting.

Another reason is perhaps a more process and technology-based one: a home purchase or sale requires a variety of stakeholders (buyer/seller, lender, insurer, inspector, agent, lawyers, etc.), and the number of point solutions required to manage a transaction across all of them is immense. The transfer of data between steps of the transaction and third parties is hard, and software is not malleable enough to read and write the data across so many systems cleanly.

All that said, agents aren’t exactly marketing their job as being the emotional support for a transaction and making sure that things move along smoothly. They’re marketing access to properties (replaced in modern times with the MLS and subsequent tech-enabled brokerages and platforms that tap into the MLS), buying and selling for the right price (in competition with AVMs), negotiating (again, in clear conflict with a buyer), and ensuring a great and stress-free experience for their clients, for example.

Essentially, they market the things they do that compete with technology and startups, and in doing so unintentionally highlight the fewer jobs that they are uniquely suited to perform.

This realization to home buyers and sellers may not drop commissions to zero, but I can’t imagine a world where an agent’s newfound emphasis on proving ‘value-add’ is going to increase the size of the commission pool. Going back to the Inman conference, there were a variety of top agents and brokers who all said the same thing: they’re in a client service industry. Their job is to go above and beyond for their clients, often in ways that have nothing to do with the transaction. This relationship piece is critical to top agents and something that will be put to the test in the coming months as the NAR settlement plays out.

The Evolution of Consumer Preferences

The NAR settlement isn’t happening in a vacuum–consumer preferences and behavior are changing in parallel.

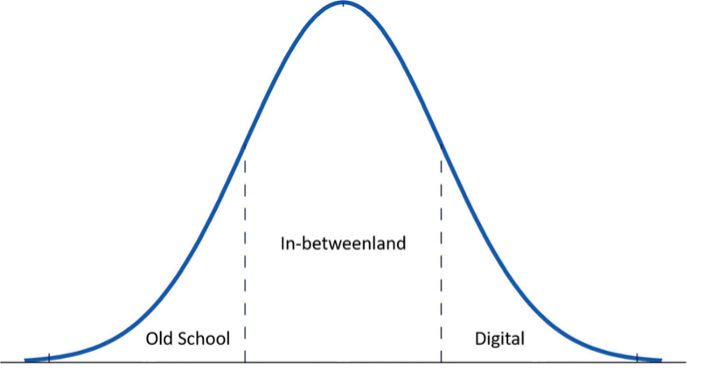

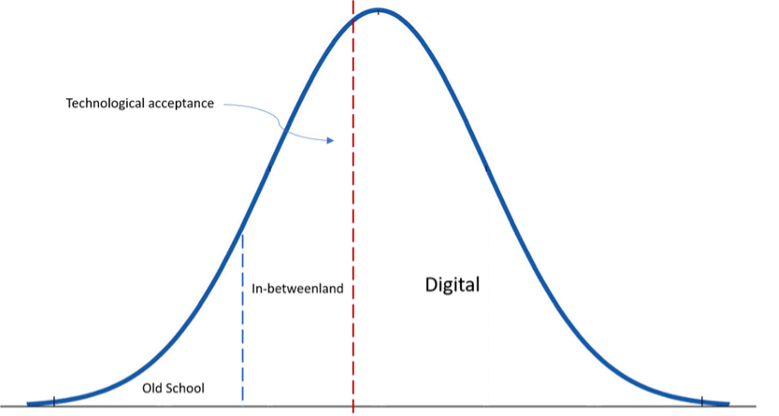

Let’s begin by taking all theoretical home buyers and sellers and lining them up based on how digital and automated they’d like their transaction to be, with one end being those that want everything to be analog, offline, manual, and run through a real estate agent that they talk to, and the other preferring entire transaction be digital and automated with no person involved at all. A normal distribution of those preferences might look something like this (‘Old School’ = analog):

Source: Nine Four Ventures

If the distribution of consumers is truly ‘normal’, then odds are good that old-school folks will be happy to work with – and pay full commission to – an agent, whereas the digital folks may never want to work with or pay an agent, with the in-betweeners…in between the two, with varying degrees of willingness-to-pay and human interaction. If you are a player in this ecosystem, pro-agent, and pro-higher commission, then you probably make the case that agents on both the buy and sell side of the industry create a lot of value and that Millennials, the largest segment of home buyers coming into the market, prefer not to do anything on their own and want to use an agent. After all, this is the largest transaction that most people will make in their lifetimes, and they really don’t want to mess it up.

Source: Nine Four Ventures

However, what if the combination of technology and generational preferences that skew more digital shift the curve to something like the above? Millennials are the largest group of home buyers and are the most digitally native group to grow into that position. Is it outrageous to think that they have different digital preferences and a different willingness to pay for an agent than the prior cohort of baby boomers? I don’t think it is, and I don’t expect it to shift to something more analog and/or old school. If an agent is ultimately doing fewer jobs – despite the possibility that the emotional and relationship pieces may be the most important and valuable pieces that software hasn’t moved yet – it also seems likely that a client would be interested in paying something less than the traditional analog norms. Layer on a home affordability problem, and buyers seem like they’re going to want to use all of the digital tools and cost savings efforts that they can.

These considerations are influenced by the concept of ‘unbundling’ the jobs that an agent does and can easily transform an agent’s pricing model from a more or less “prix fixe”/flat-rate/fixed commission one to something more variable and a la carte…and the probability of the a la carte pricing exceeding the prix fixe menu seems low (i.e. commissions and fees will drop).

If consumers are now better armed to negotiate a commission structure with their agents, a logical response from an agent would be to tailor their offerings and pricing to align with the fewer jobs that their clients want to pay for. That might be a menu of offerings or a ‘tiered’ structure that ranges from full-service to one-off tasks, where an agent could still be a backstop if needed. The agents that are in the best scenarios to win may be those that adopt some or all of the tech and tools mentioned earlier to streamline their own process flows and perhaps offer white-labeled software solutions that still allow them to get some credit. These ‘menu’ offerings would be much more malleable to consumer preferences than anything we’ve historically seen and accommodate for everything from a true DIYer to someone who wants everything done for them.

Agents, however, don’t want to put a bunch of time and effort into something and not get paid. The existing commission structure takes this risk into account, but it may not in the future. At the conference there was a fair amount of chatter about transparency between an agent and their clients to get the client to understand how much work and time the agent is putting into the sale/purchase. Doesn’t that time and effort prove their ‘value’ and that they’ve earned their commission? Maybe, but I’ll argue that it probably doesn’t.

Let’s say an agent diligently tracks their time and allocates it to all the things they’re doing for a client: they spent hours designing marketing materials, going to and from showings, pulling comps, talking to potential buyers or sellers, coordinating inspections, etc., and showed the hours and energy they spent to their client. If a buyer converted those hours into an hourly rate…is the commission justified? Or a seller could look at it with the common agent-line of “do you want your house sold for top dollar, as fast as possible, while simultaneously reducing liability for the transaction?” Then does the $15,000+ per side seem more reasonable? If someone spent little time on the transaction but was an amazing negotiator and got a buyer or seller a better price than what they could’ve or would’ve gotten otherwise, then did they earn it?

There are a bunch of scenarios here, and any calculation might make the commission look reasonable. There are also a bunch of unknowns that consumers can’t know (whether a home would’ve sold for more with a different agent, or with the assistance of a digital platform, for example). What buyers and sellers can objectively compare, however, is how the cost of each of the jobs the traditional agent did compares to a digital alternative. Where software and a bunch of zeroes and ones can do a job, it’s safe to assume that the cost will collapse to the point where price equals the market value of getting the job done. And a lot of those jobs are what are referenced above. Marketing, schedule coordination, transaction management…simple stuff for AI and software to do. Therefore, I’ll argue that someone’s willingness to pay top dollar for those jobs will be far lower than for other jobs that software has a harder time competing. There is probably a premium to apply to ‘run process’ and make sure all of the inefficiencies that point solutions might bring are taken care of, but I believe we’re approaching a point where technology will compete away profit margins and costs down on almost everything outside of relationship and peace-of-mind related jobs.

A last point around competition is that the competition to perform a job traditionally done by an agent isn’t just coming from technology – it can come from other participants in the transaction as well. Most agents aren’t going to be financial advisors and generally structure themselves to get a transaction done quickly and at the best price. Loan officers (LOs), however, have a pretty good idea of what buyers can afford and the loans they can qualify for, and LOs are in a position where they want to show value as well. I see adjacencies for them to pick off some agent jobs in the same way that a home inspector may be able to with their granular knowledge and experience about the condition of a home and what work it might require. Lawyers can structure and coordinate the transaction. Many parties involved in a real estate transaction have regulatory or financial skin in the game in ways that I will argue exceed what a traditional agent has, and they seem well positioned to do more.

In aggregate, all of these pressures point to commissions dropping until the market price of managing the relationship is met, with a smaller cost for transaction management layered on. I’ll also argue that this cost structure should drop until it is aligned with global norms. That’d be a big drop in commissions and could result in a large restructuring of the industry.

This is not intended to knock all agents. There are absolutely value-add agents who deliver day in and day out in ways that exceed their clients’ expectations and that probably deserve more than the commissions they are getting paid. I don’t believe the agent will ever go away – I expect there will always be home buyers and sellers that want the ‘white glove’ service that traditional agents currently offer – but I do believe that commissions are going to drop, and that the reduction is a needed and rational outcome. Agents that make a transaction happen that otherwise didn’t stand a chance of occurring or that exceed expectations – perhaps by bringing a net new buyer to the table, finding the right home and convincing someone to sell, or structuring a home purchase or sale for more or less than their clients were expecting – seem well positioned throughout all technology and legal weather.

Ok…so where does all of this leave us?

Circling back to the original distribution chart above, it is important to understand the distribution of commissions across agents and brokers. It’s no secret that there is meaningful concentration of real estate commissions across the industry: a few agents and brokers suck up the majority of commissions. If commissions end up dropping, those who are already winning the majority of commissions aren’t going anywhere and won’t leave the industry. However, it might be a different story for the long tail of agents that don’t historically do many ‘sides’. This agent segment seems less likely to need to adopt software and technology, be engaged in the markets they serve full-time, and generally less productive than the higher-earning segments. The decoupling of commissions combined with the increased role of technology that is doing more, and the competitive nature of the industry seem like it might make the juice less worth the squeeze. Sure, the drop in commissions may not be very material, but it isn’t going to help incentivize a lower-volume agent to want to stick around. Overall, there could be a ‘rounding down’ effect that causes some agents to drop out of the industry.. Given there are 1.5 million Realtors in the US, even a 10% decline in the number of agents is a material change.

There are a few other changes that we can hypothesize:

- Luxury-focused agents who may not do as many transactions per year, even in a good market, may not need to change much as their clients are less likely to embrace the digital + DIY/DIFM trends above

- With some of the long-tail agents dropping out of the industry and a menu of options offered for the remaining agents to service the mid-market, perhaps the remaining agents absorb the sides from the folks that left the industry and leverage technology to do more sides, albeit for fewer dollars per side

- Fewer agents doing more sides at a lower commission per side may net them similar compensation, but in a very different way. The good agents that weave technology into their process may come out ahead relative to the pre-settlement era.

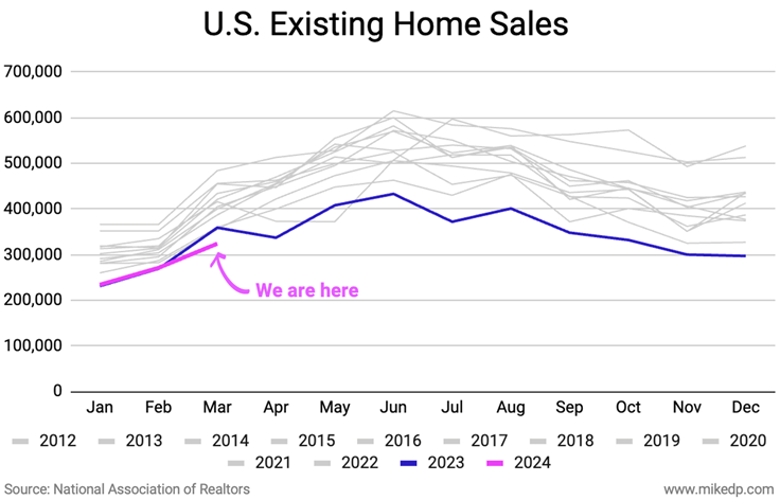

Changes to commission structure aside, we’re also experiencing a low point in the absolute number of homes bought and sold, adding additional pressure to the market:

Source: mikedp.com

2023 was a historically bad year, and 2024 hasn’t been great either. Interest rates are high and construction costs are elevated. If no transactions happen, the commission structure doesn’t matter–the industry gets hammered. With fewer transactions happening AND a lower commission per transaction, there could be a lot of agents looking for work elsewhere.

There are also looming questions and concerns that consumers may have. For example, a common pushback at Inman from agents is that there could be unintended consequences for consumers who don’t have the cash to pay their agent out of pocket. There are already some solutions being proposed to address this, however, from sellers offering ‘seller credits’ that can be used for various transaction-related expenses incurred by the homebuyer to lenders offering new products to support transaction costs. If all else fails, consumers can still revert back to the pre-settlement way of doing things.

Despite the headwinds for the agent, broker, and trade associations, I see consumers benefitting the most from all these changes. Consumers are continuing to be armed with more tools, data, and alternatives than ever before, and are finally entering a period where they have some influence over costs. As interest rates normalize, NAR lawsuits play out, and technology continues to develop, I expect we’re going to see the cost structure of the real estate agent deflate, with competition, products, and services improving the transaction and experience for consumers. It is an exciting time to be a player in the residential real estate ecosystem.