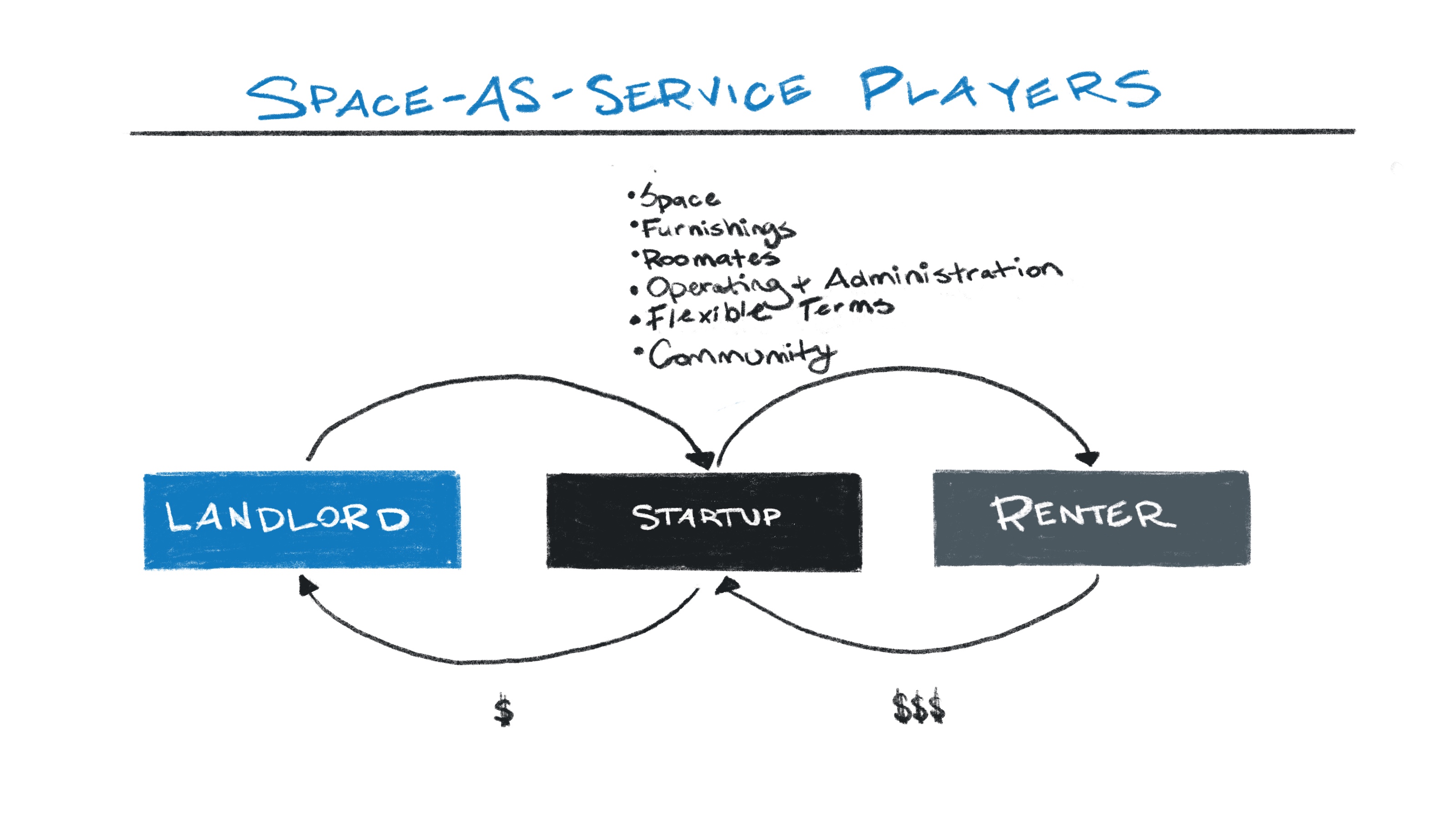

“Space-as-a-service” is a term that generally refers to an asset-light business model that allows a consumer or business to rent space that suits their needs rather than going through a more traditional capital and time-consuming buy, build, and own process.

In the office world, WeWork really brought the term mainstream by providing a space to the traditionally neglected small business owner/employee. These folks don’t usually have the capital nor the expertise needed to build out a space or the business visibility to prudently sign longer-term commercial leases. Maybe they’re attracted to coworking because they value the flexibility that a shorter-term lease can provide. Maybe they just need a desk and not an office. Maybe they value the community of other gig-economy or creative workers. What’s interesting is that it appears that many coworking renters value these elements (and many more) to the point of paying a premium for flexibility and asset-light freedom, which has interesting implications for other facets of real estate.

We’re now starting to see ‘space-as-a-service’ companies targeting multifamily real estate with similar business models as coworking companies. The reasons make sense: the business models create synergies between the landlord, startups, and renters, and doesn’t require a large change in landlord behavior for adoption.

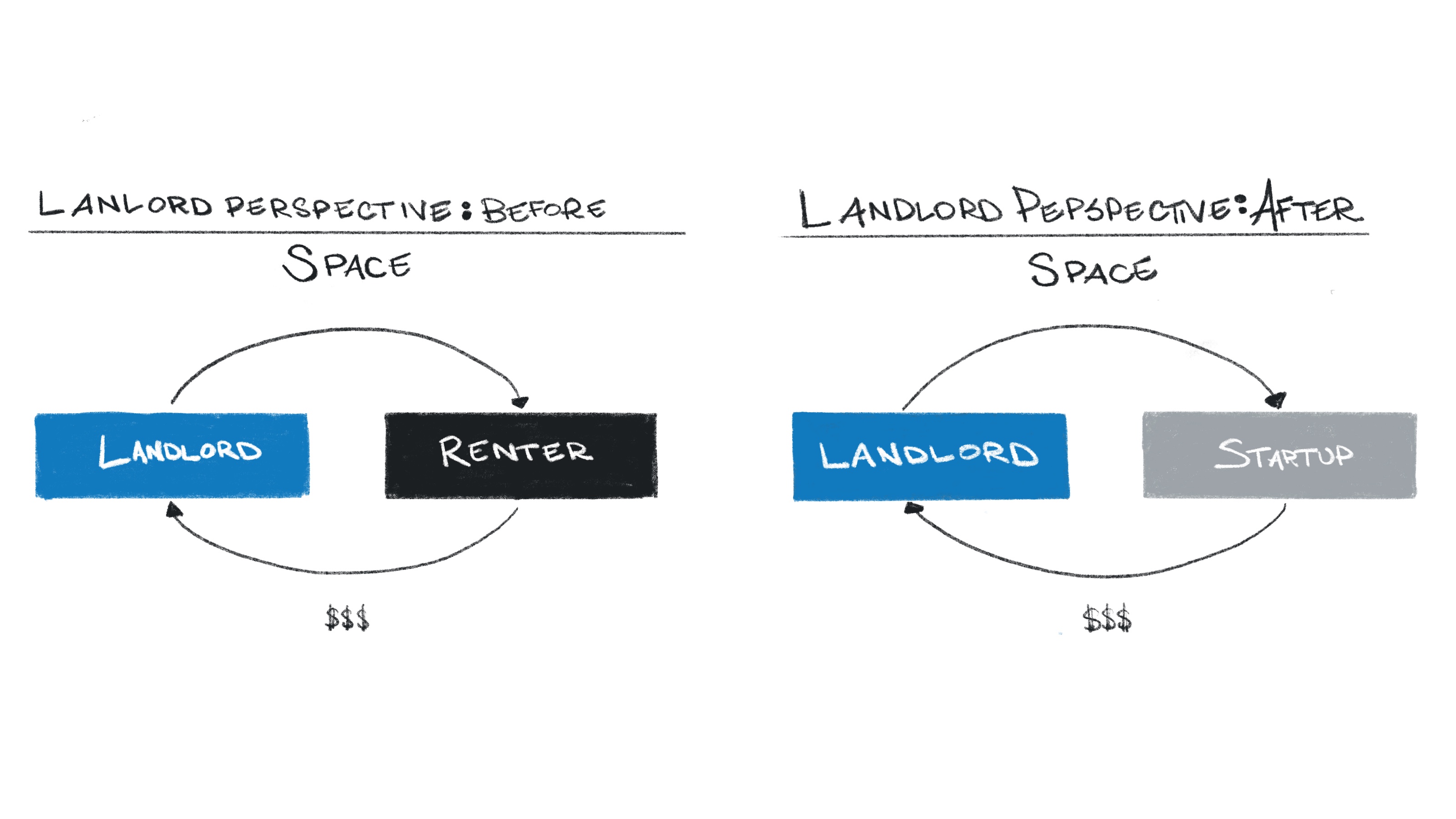

Rather than renting a single unit to a renter, a landlord typically leases several units to a startup. Landlords need to be open to the risks of allocating more units to a specific tenant (and reduce lease diversification), but there are also advantages in lowering leasing costs, saving on vacancy and agreed upon future rent increases. The process is largely the same.

The biggest impediment to adoption may be for landlords to accept that another company may be able to monetize the space they own better than they can, while likely not sharing upside. It may seem trivial but a company that leases space from a landlord will only profit if they make more money per square foot than they pay out, including costs such as furnishings, bookings, and operations. For a landlord, a downside scenario is potentially magnified relative to traditional leases to multiple tenants. More specifically, if the space-as-a-service company can’t pay rent, it could mean a whole slew of units can’t pay rent. Landlord upside is usually the same.

Regardless, the problems coworking companies are solving are similar to what plagues many apartment renters: upfront capital needed to buy furniture and for security deposits, the headache of finding roommates or coworkers to share costs and make an apartment more affordable, and the general rigidity of being asset-heavy. What this results in are co-living and shared housing alternatives with business models that more closely resemble student housing than traditional apartment rental. Rent may be per-bed, with shared common spaces, or a lighter-touch concept may just provide furniture so you have stylish furnishings and a simple move-in and move-out experience.

The multifamily space-as-a-service companies we’re seeing typically alter the following variables:

– Duration of the lease: Short, mid, and membership based

– Fully furnished, partially furnished, or furniture rental offered

– Roommates (matching)

– Price point; it’s worth noting that we’re seeing more activity in expensive, supply constrained markets, which makes sense given co-living will result in a more affordable, less expensive unit.

A supply-side wrinkle is that many companies are searching for units in traditional multifamily as well as single-family homes. In these cases, startups could be interesting partners for single family home aggregators who might be willing to try the concept on some of their homes. Other single-family home owners may be interesting in partnering with a startup if they find renting and maintaining a 4, 5, or 6-bedroom home challenging.

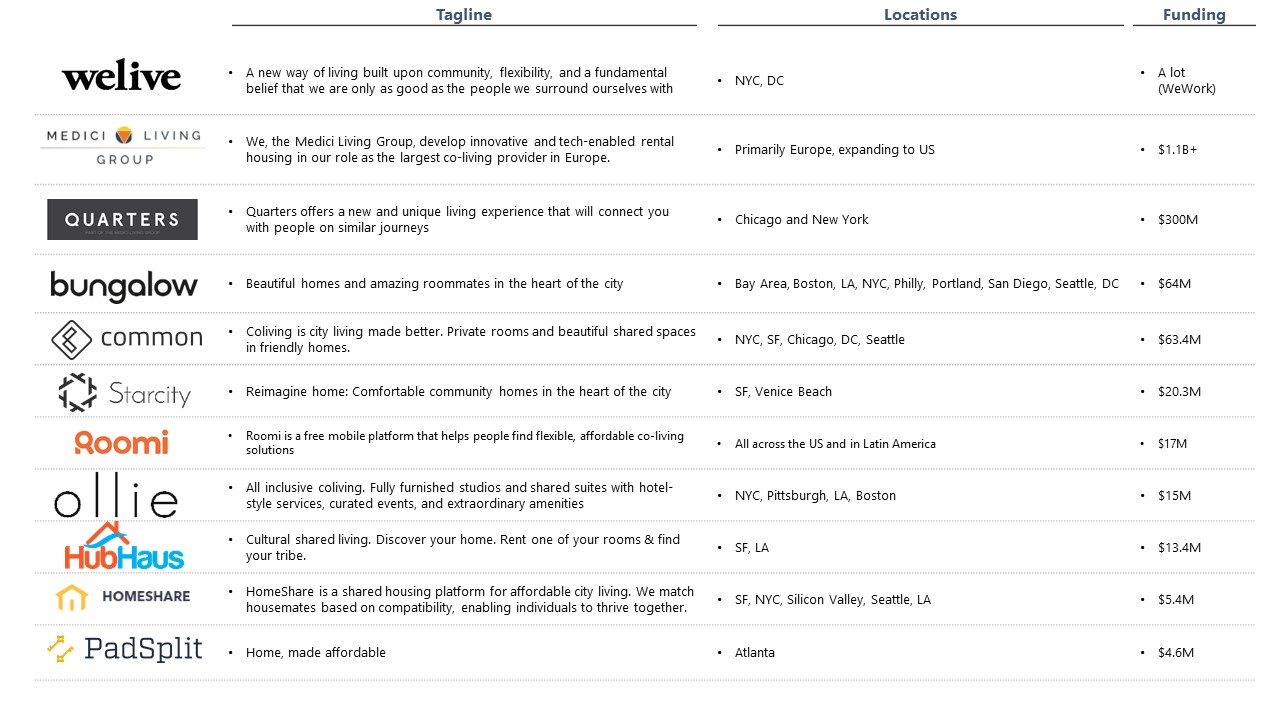

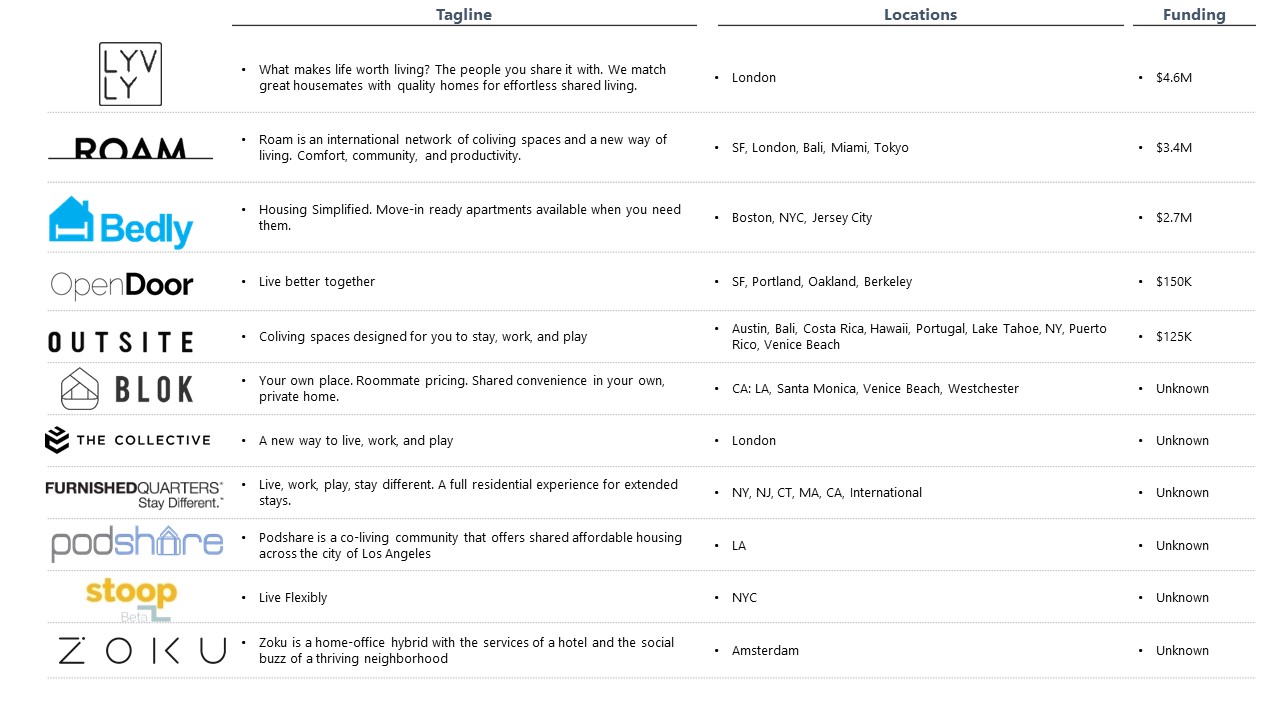

Some of the companies we’re seeing in the space (not including furniture rental or roommate matching) are: